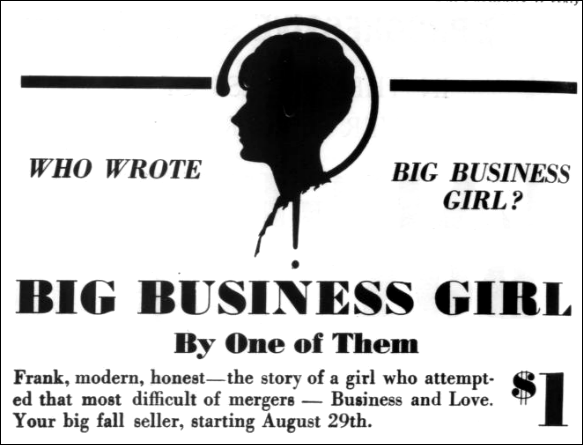

When Farrar and Rinehart published Big Business Girl in 1930, they credited the book to the anonymous “One of Them” — meaning one of the women in big business. “She knows whereof she writes. She remains anonymous because she has revelations to make and emotional secrets to tell.”

They were being disingenuous. They knew perfectly well that the author was Patricia Reilly, then managing editor of College Humor. For one thing, the novel had just been serialized in the magazine and when Warner Brothers bought the movie rights, Reilly had been named in Variety and other industry journals. For another, they’d known Reilly for years: when she was a journalism graduate fresh out of Columbia, Stanley Rinehart had hired her as a staff writer when he and John Farrar were both working for The Bookman magazine.

Though College Humor was hardly in the same league as America’s biggest weeklies, Saturday Evening Post, Liberty, and Colliers, all with readerships in millions and famous for paying extraordinary rates for fiction by the likes of F. Scott Fitzgerald, its editorial reputation belied its name. Many of the same names that appeared in the big magazines competed to publish in College Humor, even though its circulation was just 150,000 in 1930, half of what it had been before the Wall Street crash of the year before. Zelda Fitzgerald, for example, published “The Original Follies Girl” (credited to “F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald”) in the July 1929 issue, just a few months before Big Business Girl began running. Patricia Reilly would take over as editor of the magazine in 1932, moving on to run Motion Picture magazine in 1934.

When she was named College Humor editor, Reilly recalled that she felt she had to give up her own chances of being a writer when she started working at the magazine. “I wanted to write myself but I very quickly realized, and with few pangs of disillusionment, that I would never write the Great American Novel.” But sometime in 1928, she began developing an idea for a book that would blend her observations from her time in the working world with events that were shaking up Chicago, where College Humor was based. She approached Margaret Culkin Banning, already a prolific novelist and a regular contributor to College Humor, but Banning declined, saying she knew little about the situation in Chicago. She then asked H. N. Swanson, the magazine’s editor, for suggestions, and he advised Reilly to set aside doubts about her own abilities and write it herself.

Big Business Girl is the story of Claire MacIntyre:

A girl who has just graduated from a great state university, with a diploma , which is almost standard equipment for the young darling of today; a girl who faces the cold fact that nine out of ten of her number are doomed to failure, yet surveys the business world with level eyes and decides she can succeed as fast as any college trained man of her age.

Reilly’s was not the first generation of working women, but it was the first for whom going to college and continuing on to work in business was a reality for tens, perhaps hundreds, of thousands of women. There had been plenty of books written about the experience of young men leaving college and going into the world, she wrote in her foreword, but “almost never

are the problems of the girl graduate dignified between the covers of a book.”

The book opens as Claire — Mac to her friends — is celebrating her impending graduation with her boyfriend, Johnny. Johnny is a star of the campus, a singer with his own jazz band, in demand at all the local dances. He was proud of Claire for her “brains and personality” — but not her ambition. He plans to try his luck in show business and wants her to trail along as the dutiful spouse. She has other ideas. She wants to make her own money, in part because she’s racked up a debt of $5,000 getting through college.

And so, she bids farewell to Johnny and heads to Chicago, where her only relative, a comfortable but crotchety bachelor, lives. Her uncle thinks little of her plans for a career: “I think you are a crazy young kid. You have no business in business,” he tells her. After several rejections, she applies to an industrial dry-cleaning company looking to fill a new position: adjuster. The job involves settling claims from angry customers whose clothes have been damaged in the cleaning process. Today’s reader will wonder how such a job could qualify as “Big Business.” But here’s where the other half of Reilly’s concept for the book comes in.

Long forgotten in the legends of Chicago mobsters like Al Capone is the dry-cleaning racket. While best remembered for bootlegging and rum-running to supply the public with illegal booze during Prohibition, Capone and his ilk had a dozen or more other shady ways of making money. Among them was the dry-cleaning racket, which was a complicated web of collusion between mobsters and unions to shake down dry-cleaning shops and companies for protection money.

The scheme was explained a decade later in a report to the U.S. Senate:

Terrorism has been among the devices employed in the enforcement of a succession of market-sharing and price-fixing plans adopted by members of the cleaning and dyeing trade in Chicago at various times during the past 30 years. Beatings have been inflicted, trucks damaged, plants bombed, windows smashed, and clothing ruined; at least two persons connected with the trade have been murdered and the talents of such notorious gangsters as Al Capone and George (“Bugs”) Moran have been brought into play. The Chicago Master Cleaners and Dyers Association controlled the trade from 1910 to 1930, its power derived-largely from the economic strength of three friendly unions — the Laundry and Dye House Drivers and Chauffeurs Union, Local 712 of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters known as the truck drivers’ union; the Cleaners, Dyers, and Pressers Union, Federal Local No. 17742 of the A. F. of L., known as the inside workers’ union; and the Retail Cleaners and Dyers Union, Federal Local No. 17792 of the A. F. of L., known as the tailors’ union.

When he learns where Mac will be working, her uncle tells her she’s landed in the worst place in Chicago for corruption: “There are even racketeers who prey on other racketeers.”

Hired on a trial basis, Mac quickly impresses her company’s owner by running an appeal that brings in hundreds of women customers. She proves a wizard at everything from calming irate customers to convincing them to accept low claim settlements — and with the racket in full swing, fire-bombing stores and hijacking delivery trucks, there are plenty of claims to settle. The owner begins grooming her for advancement. “You don’t handle your work like a girl, somehow,” he observes. “You seem more like a man.” “That is the sweetest thing you ever could have said,” she replies. And in true chauvinist fashion, he also takes a special interest in cultivating a social relationship — purely in a fatherly way, mind, and only because his wife dislikes going out. Their home is up in Evanston, after all, and it’s so much easier for him to keep a spare tuxedo at the office.

Mac’s career is rolling along smoothly — despite having to parry her boss’s advances — when Johnny arrives on the scene. Soon, the two suitors are butting heads like a couple of buck deer in heat. And suddenly Reilly betrays her inexperience in plotting by throwing in a completely implausible twist. Johnny is upset because he and Mac are husband and wife. They were married in college. But “student marriages weren’t popular at State,” so they decided to let anyone know. Including themselves, given the way Mac and Johnny talk of parting ways at the beginning of the book.

Many of the novels about modern women and modern marriage written around this time, like Ursula Parrott’s Ex-Wife and Sarah Salt’s Sense and Sensuality, struggled to reconcile traditional notions about a wife’s role and the desire to earn money and pursue a career. The choice is often presented in either/or terms, and neither option particularly appealing.

Big Business Girl rejects the either/or choice. For Mac, abandoning her career for a domestic life is out of the question. “She wondered how women just stayed at home and shopped and played bridge in the afternoon and had tea together, with nothing to talk about except their parties and husbands and menus and clothes. She couldn’t picture herself in such a role — ever.” Johnny eventually comes to acceptance, if unmistakably grudging. Long before the acronym was invented, he sees the economic benefits of being in a DINK marriage.

In part, this was due to Reilly’s own experience. Around the time that Big Business Girl was being serialized, she married Robert Foster, a stockbroker she’d known while working for The Bookman in New York. As she told an interviewer in 1932, “My husband is all for my working. He thinks I’d simply die on the vine if I didn’t have something to keep me busy constantly.”

Warner Brothers bought the movie rights to Big Business Girl soon after its run in College Humor, and the movie version starring Loretta Young as Mac and Frank Albertson as Johnny was released in mid-1931. The adaptation was written by Robert Lord, then Warners’ most prolific screenwriter. Lord recognized that Warners could make a love story or a gangster story but not both, so Chicago was swapped in favor of New York City and dry-cleaning in favor of advertising. Young carries off her role — stunningly beautiful and full of entrepreneurial gumption. Frank Albertson is a convincing college boy and an utterly unconvincing romantic lead who makes the often-slimy Ricardo Cortez as the lecherous boss look like a good prospect. Lord takes advantage of the divorce the couple consider to write a terrific scene in which Albertson and Joan Blondell play cards in a hotel room while waiting for a private detective to catch them in flagrante.

As in the novel, the couple reunite — but with the understanding that Mac gives up business for the hope of living happily ever after with Johnny. In this way, as seems to be the case with many of the books behind supposedly outrageous Pre-Code movies, Big Business Girl is more complex, realistic, and sophisticated than its better-known film version. Even before the enforcement of the Motion Picture Association’s Production Code, Hollywood was forced, through a combination of the constraints of short running times, set limitations, and the need to appeal to a much broader audience than that of a magazine like College Humor, to eliminate much of what makes the book interesting.

Sarah Lonsdale is a journalist, critic and author. Her latest book, Rebel Women Between the Wars: Fearless Writers and Adventurers (MUP, 2020) investigates how women in the 1920s and 30s overcame social and political obstacles in a range of occupations including mountaineering, engineering and foreign correspondence. She lectures in history and journalism at City, University of London.

Sarah Lonsdale is a journalist, critic and author. Her latest book, Rebel Women Between the Wars: Fearless Writers and Adventurers (MUP, 2020) investigates how women in the 1920s and 30s overcame social and political obstacles in a range of occupations including mountaineering, engineering and foreign correspondence. She lectures in history and journalism at City, University of London.

Joanna Pocock is a British-Canadian writer currently living in London. Her work of creative non-fiction, Surrender: The Call of the American West, won the Fitzcarraldo Editions Essay Prize in 2018 and was published in 2019 by Fitzcarraldo Editions (UK) and House of Anansi Press (US).

Joanna Pocock is a British-Canadian writer currently living in London. Her work of creative non-fiction, Surrender: The Call of the American West, won the Fitzcarraldo Editions Essay Prize in 2018 and was published in 2019 by Fitzcarraldo Editions (UK) and House of Anansi Press (US).